Does “Bad Technique” Exist?

Introduction

Our understanding of movement shapes our ability to avoid and overcome pain and injury. These can be deeply personal subjects, as everybody processes pain differently and injuries can happen as a result of an infinite array of individual differences, dispositions, and unpredictabilities that we don’t yet have a machine capable of processing and calculating.

In this article, we're going to discuss an emergent shift away from the conventional models of movement and why it’s happening. This won’t just be theory, though; this will contain actionable information for everyone. With that being said, my goal is for you to strongly grasp the details of this change so you can improve your own training and recovery and develop a healthier view of how your body moves, processes and adapts to stimulus, and handles physical demands.

The Conventional Model

The conventional model of movement - the one you’re likely familiar with - is called the Kinesiopathological model (KPM), which translates to “the study of movement disease/suffering.” This model posits that faulty movements and mechanics gradually wear down tissue, leading to pain and injury, and that there are a collection of universal “dos” and “don’ts” to minimize this wear and tear. Some examples of KPM “dos” include:

A neutral or flat (or even extended) spine under compressive load:

Credit: Be Strong NKY

Keeping knees out while squatting:

Credit: Starting Strength

Externally rotated shoulders and depressed/retracted shoulder blades during pressing movements:

Credit: White Coat Trainer

Conversely, "bad" positioning would be the opposite of these - rounded back, knees caving in, elbows “flaring” during pressing, elevated/protracted shoulder blades etc.

Much of this model is built on the idea that these “dos” acutely displace load more evenly across passive tissue structures (cartilage, meniscus, spinal discs, etc) than the “don'ts,” reducing tissue deformation/damage. It’s worth pointing out that this model is deeply rooted in the conventional (aka the Biomedical) model of pain, which describes pain as feedback from damaged bodily tissue.

The New Model

The new model, frequently called “Movement Optimism,” challenges this paradigm, claiming the following:

“Dos” and “don'ts” are entirely context specific

"Correcting" technique isn't about putting the body into "safer" positions, but rather building ability to execute specific tasks and handle specific demands

Pain and injury are just as influenced by stress and recovery as they are by specific mechanics

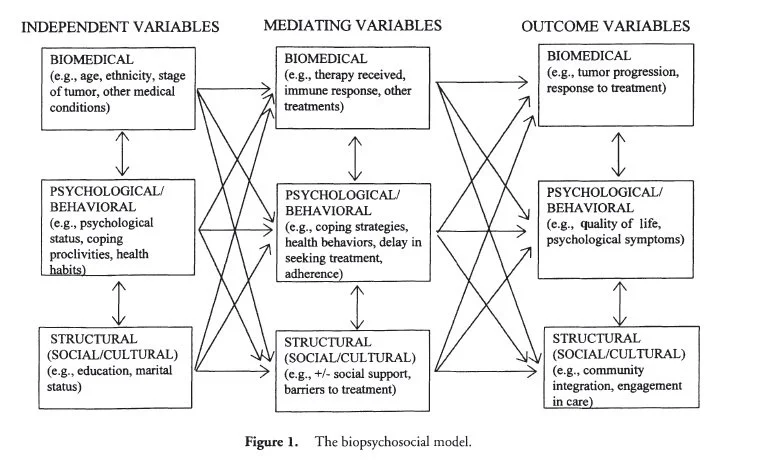

These principles are closely tied to an emerging model of pain known as the Biopsychosocial model, which states that pain results from a complex interaction of factors such as sleep, mental and physical stress, personality differences, prior experiences, and many more. Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, it proposes that pain is primarily feedforward output from the brain (called “Predictive Coding”), meaning pain often anticipates threats rather than being a direct indicator of tissue damage (which seems to be much better supported by up to date research on the subject), and this anticipation is heavily influenced by the aforementioned factors.

Credit: ScienceDirect

Interestingly enough, the Biopsychosocial model was originally proposed by George Engel in 1977 (also see reference 2 in that link) as a means of explaining all health outcomes, including cancer and disease, not just pain.

Credit: PsychologyiResearch

I highly recommend delving into the prevalence of asymptomatic disc degeneration, rotator cuff tears, and knee osteoarthritis, as well as some of the science behind Phantom Limb Syndrome to see how short the Biomedical model falls in explaining what pain is, where it comes from, and what to do about it. To summarize these links: pain often exists without tissue damage, tissue damage often exists without pain, and pains/sensations are commonly felt in amputated/missing limbs.

Largely rooted in these more updated understandings of pain and discomfort, Movement Optimism focuses on the education and demystification of movement, with the goal of fostering a more confident and robust approach to physical preparedness, pain management, and injury rehabilitation rather than one limited by fear. Instead of attempting to develop a simple pattern to predict what will and what won’t lead to pain and injury, it views these phenomena as individual, context specific cases that require unique approaches.

Pain and injury can arise from a multitude of factors beyond one’s control, and is rarely the result of a simple A→B connection. Instead, while there may be (and often is) a mechanical component to pain, there are often many other factors worth considering that may suggest a more productive approach. For instance, a high volume/effort training block can be unsustainable during busy work seasons, which can lead to joint aches and pains as a result of a lack of recovery, making it potentially more productive to scale back total training volume rather than bog the individual down with complex “corrective movement” protocols.

And to that end, Movement Optimism disclaims that while pain does not automatically indicate actual tissue damage, it remains a valid and profound experience that may warrant temporary modifications and adjustments. After all, pain can and often does alter movement habits in ways that may not be appropriate or effective for a prescribed plan or attempted goal, which is more than sufficient reason to accommodate it, even if no structural damage is present.

Why The Conventional Models Are Ineffective

The conventional models end up at odds with their own goals by fostering a vigilance about one’s every physical movement that quickly turns into movement hypochondria. It logically follows from them that when something hurts, it’s due to tissue damage, and must be rested. This approach tends to lead to either…

A frustrating cycle of resting until pain subsides, only for it to return upon reintroduction of physical demand, or

A spiral wherein the pain takes so long to subside that the tissue deconditions to an extent that it ends up in even more pain upon reintroduction of physical demand, leading to more movement restriction, and even more deconditioning, and so forth

Credit: Myself

While I can appreciate this attempt at minimizing injury probability, it typically causes more harm than good over time as it progressively shrinks the toolbox for addressing current issues as well as preparing for future ones (which only opens more doors to pain and injury). In addition to these physical detriments, this fixation on exclusion causes an undue mental burden, as it amplifies how people regard the normal and routine movements, pains, and discomforts of everyday life.

I highly recommend reading this article from the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy on the connections between fear avoidance and chronic pain, as it discusses this cycle in much deeper detail.

Why Movement Optimism Is Better

Movement Optimism Is More Encouraging

Movement Optimism ditches the aforementioned mental burden by framing pain as a neutral phenomenon that, while valid and worthy of consideration, is so complex and inaccurate in nature that it’s not always reasonable to think it’s the result of simple mechanical connections. In fact, just this simple reframing of pain can significantly improve pain prognoses, as explained here in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy.

From the Movement Optimism framework, instead of following rigid "dos” and “don'ts," you’re encouraged to figure out your own movement dispositions and limitations and adjust your program accordingly (or not!). This makes the process of building resilience, working through or around pain, and recovering from injuries more logical and intuitive and less exhausting and confusing.

Movement Optimism Is More Practical

In addition to that, in my case as a personal trainer, Movement Optimism is not only a more detailed framework to view movement through, but also a more practical one. I see people of all shapes and sizes from all sorts of different backgrounds, and there is simply no way for me to effectively apply the KPM’s reductive model at scale. Things like limb segment length, body composition, age, gender, prior training experience, current sports or hobbies, and so forth have significant impacts on how people execute movements, which trickles into how their bodies adapt and develop over time, and thus what becomes their own unique sets of “dos” and “don’ts.” The result of this is some people responding extremely positively to things that could be cataclysmic to others.

As such, a model that accounts for these differences is best, and that’s what Movement Optimism does.

Movement Optimism Just Makes More Sense

Movement Optimism’s whole point is that if injury is the illness, then physical preparedness is the medicine.

The KPM agrees that physical preparedness is necessary to prevent injury, but cuts people off from whatever preparedness would be built from training literally anything outside of its arbitrary set of “dos.” Movement Optimism simply ditches this arbitrary exclusion criteria, demanding far less mental gymnastics (in fact, none at all) to align with the real world, and ultimately working better both in theory and in practice.

Conclusion

While the Kinesiopathological Model (KPM) provides a straightforward framework linking specific mechanics to injury, it often falls short in explaining the complex reality of pain and why injuries occur beyond these simple connections. Movement Optimism, conversely, emphasizes building a wider range of capabilities and resilience by ensuring that movement prescriptions always match individual context, free from the fear-based limitations of the KPM. This approach ultimately leads to more detailed and practical approaches that truly account for the vast array of individual differences influencing what constitutes safe and effective practice. Ultimately, Movement Optimism leads to moving with greater confidence, adaptability, and a deeper understanding of the body’s capabilities.

Common Questions

In talking about this with my clients, I’ve learned that this shift can be quite daunting. As such, I want to address the most common questions and concerns I get about this model, just to set the record straight and clear up confusion. Below are some of those questions and my usual responses.

Q: So are you saying pain isn’t real?

A: Absolutely not! It just doesn’t necessarily mean there’s structural damage.

Q: So should I just ignore the pain then?

A: Nope! Pain can massively impact how you move and how you perceive movement, which makes it immensely important to take into consideration and potentially modify around.

Q: So does that mean I should stop deadlifting with a neutral spine?

A: Not necessarily! A neutral spine helps ensure/maximize hamstring and glute involvement, which are vital muscles for general strength and resilience. You just don’t necessarily need to worry if or when your spine rounds.

Q: But don’t people get hurt when they round their back?

A: That can and does happen, but people also get hurt when deadlifting with a neutral spine. There are other more influential factors preceding the injury than the position it happened in.

Q: But isn’t it bad for my knees to cave in?

A: Only if you aren’t prepared for it!

Q: So what should I do then? What do I need to change?

A: Nothing! Movement Optimism just removes limitations, it doesn’t necessarily mean you need to change what you’re doing now. It just means we’ll have access to a wider selection of fixes if or when we run into issues down the line.